Have

you ever thought about how the Bible is read? We call it the "Word of

God". Christians believe that when they are reading the Bible, God is

speaking to them. They believe that the Bible comes from God. When we read the

Bible we see God speaking to us with words, audibly, literally, and physically.

All this gives the impression that as we are reading the Bible what we are

reading are the actual words that God said to write. As if what we are reading

is the words God told some men two thousand years ago to put down on paper.

This

being the case, it seems that the most intuitive way of reading the Bible would

be to start with the assumption that everything written in it directly comes

from God. Thus, if the Bible says that squares are circles then we have to

believe that God says, "squares are circles". If the Bible says that

yodeling is for sissies then we have to believe that God says, "yodeling

is for sissies".

There

are two things which really fuel this idea. The first is that God does not lie

(Heb. 6:8). The second is that God makes clear His will (Rom. 1:25). God would

not confuse us by giving us a book which did not mean what it said. If God is

all-powerful then surely he has the ability to ensure that the interpretation

of the Word be as easy and plain as possible for readers of all time to be able

to follow its instructions. All this suggests that when we read the Bible the

primary, or preferred, method of interpretation ought to be the literal.

I

believe that this is represented by what is called Biblical Literalism, in our

day. What the Bible says ought

to be interpreted literally. Now this can be

applied differently. Some think that because they read the Bible literally it

means that the surface, or face-value meaning of the words is the authoritative

interpretation of scripture. Others think that to understand the Bible

literally means you have to delve into history to know what the author was

actually trying to say. Still others claim that to read the Bible literally we

have to harmonize, or in other words, create a hybrid text which actually

reveals to us the literal meaning of God's word. There are many ways to be

literal about the Bible, and you would think that since it is such an easy

method,or such a clear way, to know what God's will is for us today that there

would be more consensus on this matter.

In

a rather strange way, Biblical literalism forgets the very thing that makes a

book... a book. Books are not just written to be carbon copies of a persons mind,

nor are they written to be the sole representation of a past event. Books are

written to be timeless. Books are written to be immortal. Books are written to

be eternal. And when we make the Bible such an absolute authority we shed the

Bible of its mystery and depths that can only be plumed through the awareness that

God moves in ways unexpected.

When

I first came back to the Lord, I didn't want to take anything for granted, and

that especially included my Bible. I desired to understand it the way that

would contribute the most to my spiritual development and relationship with

God. I grew up in an area that is dominated by fundamentalism. Every Christian

believes that if the Bible says it then that's how God wants it, and that ends

it. There is this all to common belief among Christians that because the Bible

says something then that ought to end debate, questions, or inquiry into the

matter. This, of course, is merely an extension of the idea that the Bible

comes from God, but goes further to say that if something comes from God then

its authority is absolute.

I

began to study my Bible with this awareness that if it came from God then it

ought to have those qualities of authority and literalism that I was seeing

everywhere around me. But I found that there were certain things that what most fundamentalist Churches believed were not at all the literal interpretations of Scripture. In fact, it seemed that for the most part literal-orientated Churches were very accommodating to having symbolic or "spiritual" interpretations in those areas that were most self-serving to the Church. What I found were two very big problems. The first is

tithing, and the second is hell.

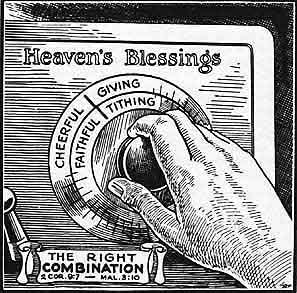

Every

church that I know of teaches tithing. Many churches do it with a Jedi mind

trick involved, but when pressed on the issue they believe that the Bible

teaches tithing and it is a thing that every Christian ought to be doing in

service to their God to support the church. I have talked to many pastors on

this issue, and have come to this conclusion fairly. This means that according

to the dominant view of the Bible proposed by the church I ought to be able to

read the Bible literally enough to determine that tithing is what God expects

of me. If I read the Bible literally and it does not conform to what most

churches say then it would seems that I either need to abandon the Bible all

together on the assumption that the only appropriate interpretation is the

literal, and hence Christianity, or that I need to reconsider what the

appropriate method of interpretation actually is.

The

word "tithe" is only mentioned twice in the New Testament. It's not

in the Epistles, which are dated earlier. The two times it is mentioned come

from the same story. Matthew and Luke both tell the story which means that the

New Testament only, really, has one mention of the word tithe, and here it is:

"Woe to you, scribes

and Pharisees, hypocrites ! For you tithe mint and dill and cummin, and have

neglected the weightier provisions of the law : justice and mercy and

faithfulness ; but these are the things you should have done without neglecting

the others" (Mat. 23:23).

Now

in reading the Bible literally it is important to not dismiss this verse simply

because there is only one mention of it. Jesus is clearly advocating tithing,

which means that we should assume God is advocating tithing. But to simply

single out this one aspect of this verse would be to pick and choose what can

be literally seen in this verse. Another thing which is clearly in this verse

is that Jesus is speaking to the Pharisees, or he is speaking about the

Pharisees. The other thing to notice is that Jesus is speaking about past

events. He is not saying that the Pharisees should tithe in the future, he is

saying that in the past Pharisees should HAVE tithed without neglecting

justice.

This

does not negate the force of what Jesus is saying about tithe. But it does give

us some considerations that need to be addressed. First, Jesus is not giving a

direction to his disciples as to how he wants them to behave. In fact, when it

comes to giving the only thing Jesus directs them to is the widows

"mite" (Mark 12:43). Jesus could have taught them about tithe at that

moment, but he didn't.

The

reality is that the New Testament church did not practice tithing. Jesus' words

are hardly indicative of any normative quality in the lives of the believers,

and Christ only offers those words as a critique of a group of people that existed

outside the influence of those who followed Him. If we are going to take Jesus'

words concerning the Pharisees as normative for Christians today then we might

as well take seriously his call for the "Rich Young Ruler" to sell

all he owns so that he could follow Jesus (Mark 10:21).

Plus,

we do have many teachings in the Epistles as it concerns generosity, giving,

and supporting the church that makes no mention of tithing (1 Cor. 16, 2 Cor.

8-9). Paul tells believers to decide in their hearts what to give. He tells

believers that giving should not be a burden for the poor. The rich should give

more, and the poor should not be expected to give. Paul's teaching on giving is

vastly different then the teaching on tithing. Paul had plenty of chances to

call his teaching on generosity an extension of tithing, but he did not.

As

far as Paul was concerned tithing was simply a part of the Law which was over,

finished, ended (Gal. 3:25). Interestingly enough, if we are going to take a

literal position on tithing then we would have to apply the same understanding

to tithing as it was represented in the Bible. Clearly, tithing has nothing to

do with the New Testament. So if Christians are expected to tithe based on the

literalness of the Bible then we should see what the Bible literally says:

" 'A tithe of

everything from the land, whether grain from the soil or fruit from the trees,

belongs to the LORD; it is holy to the LORD." - Leviticus 27:30

What

was the tithe? And what wasn't it? The tithe was not income based. In a market

economy the tithe is almost entirely senseless. The tithe only applied to

landowners. And it only applied to farmers and herdsmen. Whatever the land

produced either in produce, or animals was considered as tithe-worthy. This is

the literal meaning of tithe. It was not a universal, all encompassing, command

on the people of Israel. In today's society it would be business owners who

paid the tithe, but that is only conjecture.

What

the Bible tells me about tithe almost turns the whole enterprise of the church

on its head. A Church which both accepts tithes and promotes Biblical

literalism is making such an affront to border on blasphemy, but we do not have

to go that far. But one word definitely seems applicable. Hypocrite.

Tithing

is one thing that no literalist can actually take literally, it simply does not

seem possible, but it is very likely that most literalists believe and practice

tithing. Thus, if the application of symbolic or "spiritual" meaning

in the Bible is to be limited as much as possible it seems that this dictum is

not followed at all when it comes to tithing. Why not simply follow, preach,

and teach what Paul says in the Corinthian epistles? Why make it more

confusing? More complex? My desire for simplicity was helping me see how easy

the first believers tried to make things on the early church. But I still

needed to know how to find direction two thousand years later.

It

seemed that Biblical literalism had a strike against it.